Last summer, I was sitting at the bar before a comedy show, when my friend looked up from his phone and asked me what I thought about the latest comedy drama happening online: a New York comedian was getting death threats for a joke she had made.

“Oh no!” I said, “What happened?” I could feel a tiny spike in my heart rate, which is not unusual for someone like me. Most comedians I know are enthralled by comedy drama. We are drawn to it like Real Housewives are drawn to yachts filled with women they despise.

Before my friend could describe the incident, his eyebrows lifted.

“Oh? You don’t know?” he said, “I figured you would have already posted one of your famous Sara Schaefer threads about it!”

Famous Sara Schaefer threads? I wanted to crawl under the bar and die. The phrase stung, because just a few weeks prior, I had gotten into a major twitter fight with a handful of comedians and their fandoms. It was over one of those “famous Sara Schaefer threads,” in which I had proclaimed that booking Louis CK was boring. This had angered some comedians and their loyal fans and resulted in a week of taunts, harassment, threats, and embarrassment. It had also kicked off one of the worst anxiety attacks of my life.

“I don’t do those anymore,” I said to my friend. The words came out bitter and quick. It was not some grand declaration, but instead a hurried defense against what I had already feared was becoming my reputation: that I was a comedian not known for being funny, but instead for arguing.

Once I said it out loud, though, the idea grew into a conviction. Later that night, I decided I was really done arguing online about comedy.

And goddammit, I picked a terrible time to quit. So many juicy comedy debates awaited me. SNL drama! Famous comedians complaining about being “cancelled” in stand up specials they got paid tens of millions to make! Comedians saying dumb shit weekly! A journalist even declared that there was a “comedy civil war” happening! And I couldn’t comment on any of it!

At times, the urge to join the battle was so intense that I would type and erase tweets over and over, practically sweating as I resisted the temptation to engage once again. But each time, within 24 hours after the debate had died down, I would feel like I had just climbed a mountain. I had done it! I never once have regretted not commenting on a comedy debate. The enormous relief I have felt has been undeniable. No more obsessing over what I had posted, no more reading cruel words meant to intimidate and hurt me, no more panicking over what it might do to my career, what my peers might think of me, and if I am on the Right Side or the Wrong Side.

And once you step back from it, it’s hard not to see the con. I started noticing the pattern:

Comedian does or says something to intentionally stir up a reaction.

The “woke mob” responds accordingly.

The comedian now elevates and draws attention to this negative feedback (usually by quote-tweeting, so all their followers see it more easily), and they add something along the lines of “Seeee? They’re trying to ruin comedy!” or "Cancel culture is destroying us!” or “Get her, boys!”

The comedian’s fans are now activated, and the war is on.

Other comedians join in the fight, often issuing black-and-white decrees demanding fealty: “If you don’t love [Comedian Name], you hate comedy.” or “Any comedian who is not defending [Comedian Name] is not a real comedian.” Now, there is a threat of career consequences, as our business is so tightly linked to social status. Outcasting is a weapon comedians love to wield.

In the aftermath, the original offending comedian may or may not issue an apology, but either way, they have “won.” They’ve fulfilled their own prophecy, united their fandom behind them, and continued on with a narrative that fosters more loyalty, more subscriptions, and more tickets sold.

It’s easy to apply this pattern to other areas of public discourse as well, especially to politics. The arguments are always the same, with the same points volleyed back and forth again and again, with no minds actually changed, and the whole thing, like a Louis CK booking, has become woefully predictable.

I realized that by fighting these types of fights online, I was just playing the part they wrote for me, and for what? I used to tell myself that I was standing for something. I thought I was using my voice to speak up for myself, for women, for comedy, and even for free speech; after all, free speech is not something reserved just for the “edgy” comedian. It should be something we all enjoy.

Also, and here’s the insidious part: I had come to unconsciously believe that getting into these types of online arguments were actually beneficial to my career. My “famous” threads would indeed get a lot of retweets. I thought, for a time, that this was because these were of a better quality than my other types of tweets; the positive feedback could only mean I was doing something right. Other stuff, like jokes about mundane topics, or anything nuanced, would get less attention. I figured that was because those tweets were not as “good.”

But after years of trying to use the platform to build more followers, and experimenting with how I used it, it became clear the platform was using me. It is very obvious to me now that Twitter is intentionally built to reward big opinions and piping hot takes. The reason these types of posts are rewarded is because all-or-nothing, inflammatory statements invite the most engagement. And there is nothing the social media corporations want more than for you to stay engaged. An employee at Facebook once told me that their algorithm rewards native video and pictures, and buries anything that would encourage someone to click to an outside link and leave their site. These companies spend a lot of money figuring out new ways to manipulate our brains and take us hostage.

If you’re not sure what I mean, answer this: which statement below is going to get more engagement?

1: “I don’t like the new Beyonce song. But I can totally respect someone that does, after all, taste in music is subjective.”

or

2: “BEYONCE IS TRASH.”

Obviously, number two. (For the record, I do not endorse either statement one or two, because Beyonce Is Perfect.)

It’s not just that the opinion in statement two is very strong, but it is also that the opinion is lacking detail. The flatter the statement, the more easily it will anger and provoke. It is now open to all kinds of interpretation, i.e. more engagement! On top of all this, the human being behind the statement now lacks detail as well, and becomes a symbol, The One Side Of The Argument, which is much easier to attack and threaten. This is all by design, and it creates the perfect conditions for bad actors - whether foreign or domestic - to take advantage of us along the way.

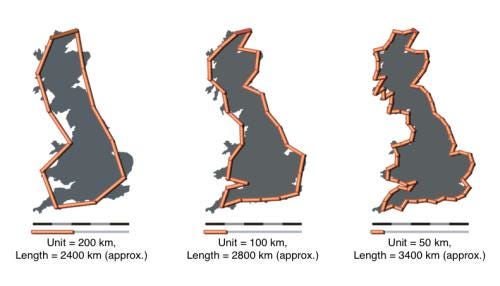

When I was traveling in the UK a few years ago, I came across some display in some museum. It showed a map of Great Britain, and discussed the length of its coastline. From far away, if you were to measure the coastline with a large ruler, it would be much shorter than if you were to get closer and measure it with a number of smaller rulers and add up those lengths. Here’s a picture to show you what I mean:

This was first observed by mathematician Lewis Fry Richardson and is known as the “coastal paradox,” and is an entry point for understanding fractals. If you keep zooming in, a coastline is infinite.

Human beings, I think, are also infinite. But online, we are being measured by impractical and awkwardly broad measuring sticks: do we support this candidate or that one? Do we tell woke jokes or edgy jokes? Do we love free speech or do we hate it? Do you wash your legs or are you a filthy pig who skips that part? Pick one.

Every day, there is a new way for your whole self to become reduced to merely a side in an argument. Online, we become shapeless blobs.

In person, the nooks and crannies of our personalities are more visible: the crows feet around our eyes emerge when we are just kidding, our voices waver ever so slightly when we aren’t sure if what we’re saying is factual or not. There are the pauses, the sighs, the tension and the breaking of that tension. The possibility of being punched for what you say, the possibility of being hugged as well. The infinite ways you can simultaneously like and loathe someone.

Real life interactions can be uncomfortable and messy, which is why I think social media is so alluring at times. It can help simplify the world, and you can feel safe and righteous as a faceless member of A Side In An Argument. That is, until you are standing alone as the target of A Side. You are now the symbol of what they fear, hate, and must defeat.

After being told last summer over a hundred times that I was “too ugly” to be sexually assaulted, I had to ask myself, what am I accomplishing here? Nothing. Nothing, except enriching people who at best are using me, or at worst, straight up hate my guts.

Ultimately, Twitter does not give me a place to shout. It gives me a place to make my voice small. I still use it for throwaway thoughts and promotion, but if you want to know how I really feel about something, you’ll need to seek me out elsewhere. And if we meet in person, I’m happy to deliver one of my famous Sara Schaefer threads, and I promise, it will be infinite.

The Schaefer Dispatch is the only email I receive that I enjoy and look forward to (okay, apart from eBay shipping updates)- I save it for lazy Sunday mornings and read it with my coffee.

This was a great read.